Story: Wentworth Woodhouse sits on an old colliery ground and is not to be mistaken for all the other Wenthworths scattered across the country. A once Prime minister of this country, Lord Rockingham lived in Rotherham. He ushered in the Independence of America and looked at plans to make Jamaican ports more financially lucrative. We know what this leads to. Ties that bind.

The recovery: Kedisha makes it clear with her assessment of the house that we need to make sure those threads continue to be illuminated. Inspired by the house and history, her beautiful wallpaper hangs like another of the house’s tapestries. Here though she honours the Black servants whose absences and silences are glaring amongst Wentworth’s detailed inventory and records of the Georgian era, leaving us enough space to imagine the rich details of their lives.

My thoughts went immediately to William Blake’s poem The Little Black Boy and a previous discussion I had comparing this with Bob Marley’s Redemption Song. How both Blake and Marley, poets and prophets, their songs of innocence and experience, their emancipation from ‘mental slavery’.

In the poem “The Little Black Boy” expresses his sadness and hardship of his earthly position existing as a black boy. Written around the time of the Wentworth male servants detailed would have lived at the house, this sadness I felt in thinking of their existence in the grand stately home. Later in the poem he reassures the English boy that because of the worldly suffering he has endured he is now equipped to shade him from the heat, which I feel is a beautiful coexistence and a sense of emancipation.

This space of emancipation, innocence and experience felt like a safe space to begin retelling their story’s. How their presence changes the narrative, creates new possibilities, and has legacy regardless of what is or is not recorded. Adding a new layer to their existence, one that includes them in the fabric of Wentworth’s deteriorating walls, whilst leaving space for what can be imagined.

Notes from Sheffield City Archive:

Wentworth Woodhouse is one of the grandest Georgian houses in England. It is situated in Wentworth, Rotherham with 87 acres of gardens and grounds. The current house was built for the 1st Marquess of Rockingham from c.1725. The family and estate papers of the Wentworth, Watson Wentworth and Fitzwilliam families of Wentworth Woodhouse are at Sheffield City Archives.

Unlike its neighbour, Wentworth Castle, the house did not directly profit from the slave trade, but there are less visible or tangible connections to historic slavery at the house.

Wealth is indelibly linked to colonialism and the pineapple - an early example of a global commodity, is an undoubted symbol of colonialism, one of the trophies brought back from conquered territories. Pineapples were a symbol of wealth and status. They were expensive and difficult to obtain, so only the very wealthy could afford them. While the pineapple fascinated Europeans as a fruit of colonialism –prized for their exotic qualities and rareness - they were not successfully cultivated in English gardens until the 1700s. At Wentworth Woodhouse, the 1st Marquess mentioned the growing of pineapples (or ‘pine-plants’) in 1737 when he noted that they were then ‘very scarce in England’. By 1740 he said that he had got their cultivation ‘to great perfection’, sending some to his London residence as centrepieces for dinner parties (Sheffield City Archives: WWM/R/3/2/2).

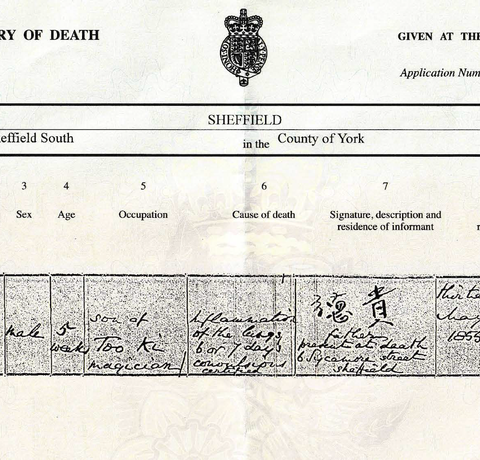

The gentry of eighteenth-century were keen to be seen as wealthy (and worldly) and one of the most sought after status symbols was a Black servant - a conspicuous sign of wealth which conveyed an exoticism and rarity (much like pineapples) designed to impress guests. Wentworth Woodhouse (and the family’s other residences) had Black servants in the 1700s. The account books at Sheffield City Archives reveal a whole ecosystem of payments designed to run a wealth household, from the supply of brass fittings for Lady Rockingham’s commode to the vast quantities of bread and eggs consumed weekly.

Among the accounts are payments made to ‘the Blacks’ - wages paid to ‘Romulus’ and ‘Remus’, two Black boys gifted to Lady Rockingham by the former Governor of New Hampshire, John Wentworth by way of thanks for looking after his wife and son (Sheffield City Archives: WWM/A). The boys worked at the London residence in Grosvenor Square and accompanied Lady Rockingham as her footmen. There were other Black servants within the household, both in London and Yorkshire.

Signed receipts for payments to Remus Stansfield and Romulus Wimbledon, Footmen, 31 Aug 1782 (Sheffield City Archives: WWM/A/1202)